Sourdough bread offers a unique crust, a tangy flavor, and an airy texture. Behind every delicious loaf lies a bubbling, living ecosystem known as a sourdough culture or starter. This simple mixture of flour and water is far from inert. In fact, it hosts a complex community of wild yeasts and beneficial bacteria. These microbes work together in a fascinating partnership. They transform simple ingredients into a flavorful, nutritious, and easily digestible bread. Understanding this microbial world reveals the true magic of sourdough. Source

. The Science of Sourdough: A Cu…

The Living Heart of Sourdough

A sourdough starter is a culture of microorganisms from the environment. Bakers create it by mixing flour and water and allowing it to ferment. Wild yeasts and bacteria, naturally present on the flour and in the air, colonize this mixture. Over several days of regular feeding with more flour and water, a stable and active culture develops. This culture becomes the natural leavening agent for the bread. It replaces the need for commercial baker’s yeast.

This process harnesses the power of nature. Each starter is unique to its environment. Therefore, the specific microbes in a San Francisco starter will differ from those in a European one. This variation contributes to the distinct regional flavors of sourdough breads around the world. The baker’s role is to nurture this ecosystem. By providing regular feedings, they ensure the microbes thrive and are ready to leaven dough.

A Symbiotic Partnership

The magic of sourdough fermentation lies in the symbiotic relationship between two main types of microbes: wild yeasts and lactic acid bacteria (LAB). These microorganisms are not competitors. Instead, they form a cooperative community where each benefits the other. This teamwork is what gives sourdough its signature characteristics.

The yeast primarily handles the leavening. It consumes the sugars in the flour and releases carbon dioxide gas. These gas bubbles get trapped in the dough’s gluten network, causing it to rise. Meanwhile, the lactic acid bacteria also consume sugars. However, they produce lactic and acetic acids as byproducts. These acids provide the classic tangy flavor of sourdough. Furthermore, the acidic environment created by the LAB helps protect the culture from spoilage microbes, making it a robust and resilient system. The Kitchn: How to Make Sourdo…

The Role of Wild Yeasts

wild yeasts are the engines of leavening in sourdough. Unlike the single strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae found in commercial yeast, a sourdough starter contains a diverse population of wild yeast species. These yeasts are hardy and well-adapted to the acidic conditions of the starter. They work more slowly than their commercial counterparts. This slower fermentation process allows for more complex flavor development in the dough.

As the yeasts metabolize carbohydrates, they produce CO2 and ethanol. The CO2 creates the open, airy crumb that bakers prize. The ethanol contributes subtle, fruity, and floral notes to the bread’s final aroma and taste. This slow, natural rise is a hallmark of traditional bread-making. King Arthur Baking: Sourdough …

The Power of Lactic Acid Bacteria

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are the primary flavor producers in a sourdough culture. They outnumber yeasts significantly, often by a ratio of 100 to 1. These beneficial bacteria are responsible for the fermentation that produces organic acids. The two main acids are lactic acid, which imparts a mild, yogurt-like tang, and acetic acid, which provides a sharper, more vinegary flavor.

The balance of these acids depends on factors like hydration and temperature. A warmer fermentation, for example, tends to favor LAB that produce more lactic acid. Conversely, a cooler, longer fermentation can increase acetic acid production. This allows bakers to manipulate the flavor profile of their bread simply by adjusting their process.

The Health Benefits of Natural Fermentation

Sourdough is more than just a tasty bread; its unique fermentation process unlocks several potential health advantages. These benefits make it a compelling choice over breads made with commercial yeast.

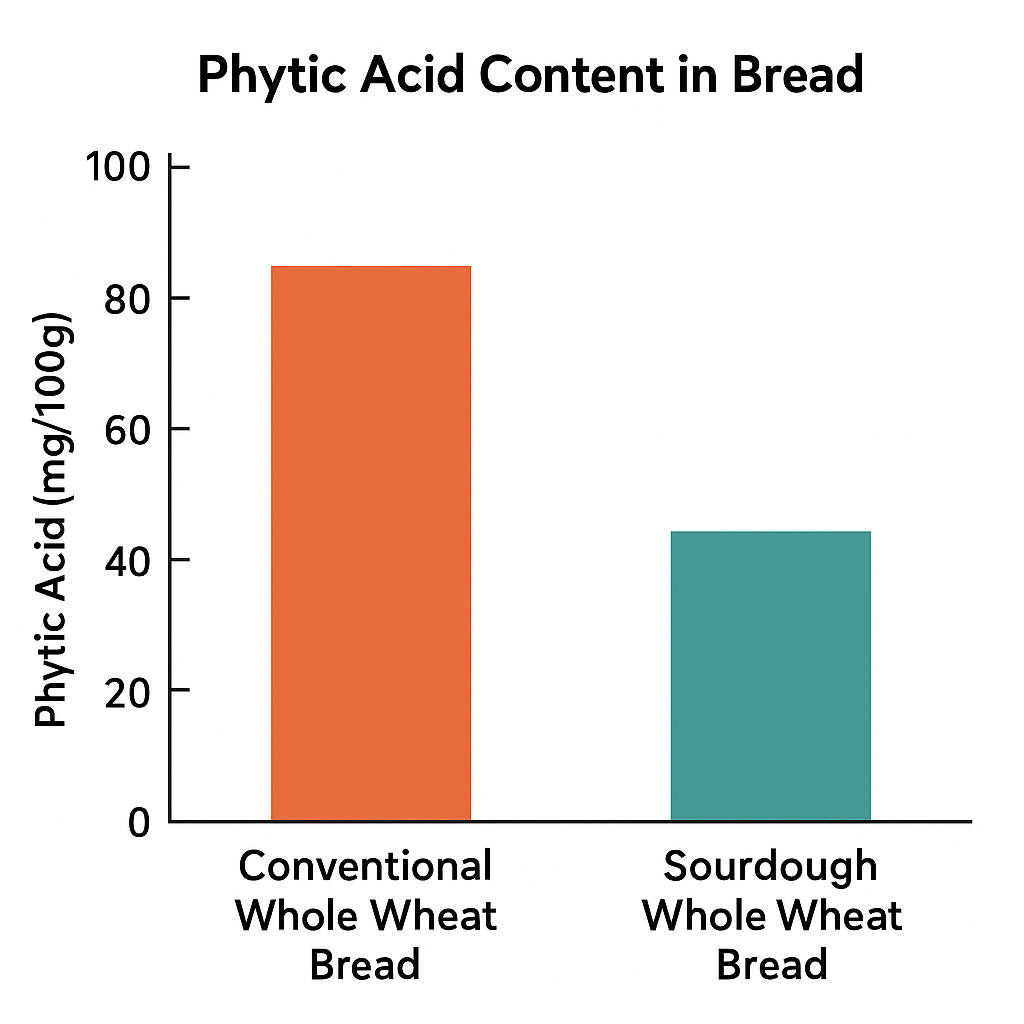

First, sourdough is often easier to digest. The long, slow fermentation process helps break down gluten into smaller, more digestible components. For some individuals with non-celiac gluten sensitivity, this can make sourdough bread more tolerable. Additionally, the fermentation process reduces levels of phytic acid. Phytic acid can bind to minerals and prevent their absorption. . Source

. Sourdough Bread: A Culinary Tr…

Furthermore, sourdough bread typically has a lower glycemic index (GI) compared to other types of bread. The organic acids produced during fermentation slow down the rate at which starches are digested and absorbed. This results in a more gradual rise in blood sugar levels after consumption. This quality makes sourdough a potentially better option for maintaining stable energy and managing blood sugar. The fermentation also creates prebiotic compounds that can help nourish beneficial bacteria in your gut, contributing to overall digestive health.

In summary, the world of Sourdough Bread: A Global Culinary Journ… is a beautiful example of microbial teamwork. The partnership between wild yeasts and bacteria not only creates a delicious bread with complex flavors but also offers tangible health benefits. By understanding the science behind the starter, we gain a deeper appreciation for this ancient and rewarding baking tradition.

A high-quality glass container is essential for maintaining your sourdough starter, allowing you to monitor its activity and health while keeping it fresh. Sourdough Starter Container Glass. This complete starter jar kit provides everything you need to begin your sourdough journey, including a wide-mouth jar and helpful accessories. Sourdough Starter Jar Kit. Monitoring temperature is crucial for sourdough success, and a reliable thermometer helps you maintain the ideal conditions for your starter. Sourdough Starter Thermometer. A dedicated warmer mat ensures your starter stays at the perfect temperature, especially important in cooler environments. Sourdough Starter Warmer Mat. Precise measurements are key to consistent sourdough results, and a digital kitchen scale ensures accuracy in every recipe. Digital Kitchen Scale. Testing pH levels helps you understand your starter’s health and activity, giving you insights into its fermentation process. Sourdough pH Test Strips. An established starter culture from around the world can jumpstart your sourdough baking with unique flavor profiles. Sourdough Starter Culture International. Wide-mouth glass jars with secure lids are perfect for storing and feeding your sourdough starter while keeping it visible. Glass Storage Jars with Lids. A cast iron Dutch oven creates the perfect steam environment for achieving that coveted crispy, golden sourdough crust. Dutch Oven Cast Iron Sourdough. A banneton proofing basket helps your dough maintain its shape during the final rise while creating beautiful patterns on your loaf. Sourdough Banneton Proofing Basket. A scoring lame with sharp blades allows you to create beautiful decorative patterns and control how your bread expands during baking. Scoring Lame with Blades. A bench scraper is an essential tool for handling sticky dough, dividing portions, and cleaning your work surface. Bench Scraper Dough Cutter. High-quality parchment paper prevents sticking and makes transferring your dough to the oven effortless. Parchment Paper Baking Sheets. A sturdy cooling rack allows air to circulate around your freshly baked bread, preventing a soggy bottom and ensuring even cooling. Wire Cooling Rack Stainless Steel. A baking stone or steel provides consistent heat distribution, helping you achieve professional-quality sourdough with a perfect crust. Baking Stone Pizza Steel. A comprehensive sourdough cookbook provides detailed recipes, troubleshooting tips, and techniques to elevate your baking skills. Sourdough Bread Cookbook. This artisan baking guide offers advanced techniques and recipes for creating bakery-quality sourdough at home. Artisan Sourdough Baking Book. A detailed starter guide helps you understand the science behind sourdough and troubleshoot common issues. Sourdough Starter Guide. Professional bread baking books offer insights from master bakers, helping you refine your technique and expand your repertoire. Professional Bread Baking Book. Understanding the science behind sourdough fermentation helps you make informed decisions about feeding schedules and temperature control. Sourdough Science Book. A techniques book provides step-by-step instructions and visual guides for mastering various bread-making methods. Bread Making Techniques Book. A troubleshooting guide helps you identify and fix common sourdough problems, from weak starters to dense loaves. Sourdough Troubleshooting Guide.

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.