The crackle of a perfectly baked crust, the soft, airy crumb, and that unmistakable tangy aroma—the French loaf is an icon of global cuisine. But this world-famous bread is not a modern invention. Its story is a remarkable journey that begins not in a chic Parisian boulangerie, but in the rustic settlements of Roman Gaul over two millennia ago.

At the heart of this history is pain au levain, the French term for sourdough. More than just a name, ‘levain’ carries the cultural weight of tradition, patience, and the very essence of French terroir. It represents a living connection to the past, a slow and natural process that stands in stark contrast to the haste of the modern world.

This is the story of that connection. We will trace the historical evolution of sourdough from its introduction by Roman legions in ancient Gaul, through its preservation in medieval monasteries, its refinement during the Renaissance, and its revered status in the artisanal bakeries of modern France.

The Ancient Loaf: Sourdough’s Arrival in Roman Gaul

From Greek Traders to Roman Legions

Long before France was France, the land known as Gaul was home to Celtic tribes whose leavening agent of choice came from their beloved beer, or cervoise. But the Mediterranean world baked differently. Around 600 BCE, Greek traders established a port in Massalia (modern-day Marseille), introducing the concept of leavened bread culture to the region.

However, it was the Roman conquest beginning in the 2nd century BCE that truly cemented a new baking tradition. The Romans, who considered beer-leavened bread to be inferior and heavy, brought with them their preferred method: natural fermentation using a levain, or sourdough starter. For Roman soldiers and colonists, this method was practical and reliable. It required only flour and water, capturing the wild yeasts in the air and grain to create a stable, flavorful, and long-lasting loaf—perfect for sustaining legions and settling a new province. Sourdough had arrived, and it was here to stay.

The Science and Simplicity of Gallo-Roman Baking

The process used by Gallo-Roman bakers was a masterpiece of natural science. A simple mixture of flour and water, left to its own devices, becomes a thriving ecosystem. Wild yeasts, naturally present on the grain and in the Gallic air, feast on the flour’s sugars, producing carbon dioxide that makes the dough rise. Simultaneously, Lactobacillus bacteria produce lactic and acetic acids, which not only create the signature tangy flavor but also act as a natural preservative, protecting the bread from mold. This simple, effective method became foundational to the sourdough evolution in ancient France. The Roman Gaul sourdough bread history is one of practicality meeting nature, creating a food staple that would define a culture for centuries to come.

The Unyielding Rise: Sourdough’s Vital Role in Sustaining Life and Fostering Resilience Amidst Famine, War, and Disease in Medieval France

Preserving a Tradition in Monasteries

With the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Europe entered a period of upheaval. Many Roman technologies and cultural practices were lost, but the art of baking with a levain found sanctuary behind stone walls. Monastic communities, as centers of knowledge and self-sufficiency, became the custodians of baking tradition. Monks meticulously maintained their sourdough starters, preserving the techniques for creating wholesome, nutritious bread that sustained their communities and the travelers who sought their aid.

The Practicality of Pain au Levain

In the medieval world, food preservation was a matter of life and death. Here, sourdough’s natural acidity gave it a distinct advantage. A pain au levain could last for a week or more without spoiling, making it an indispensable staple for everyone from peasants to lords.

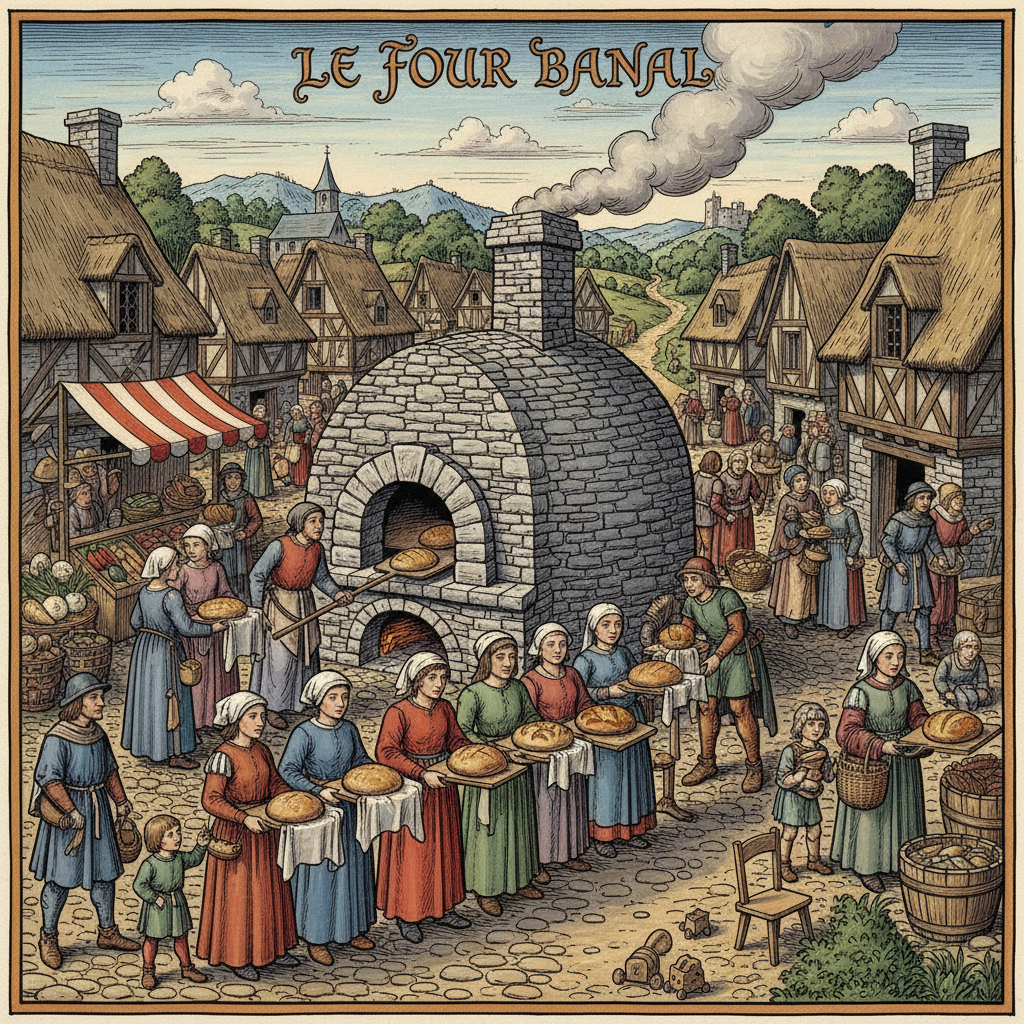

Village life often revolved around the four banal, or communal oven. Families would prepare their dough at home and bring it to this central oven, owned by the local seigneur, to be baked for a fee. This shared experience solidified bread’s role at the very center of the community. The medieval French sourdough bread origins are rooted in this practicality and communal spirit—a food that was durable, nourishing, and brought people together.

A Renaissance of Refinement: French Baking from the 1500s

Levain vs. Levure – An Old Debate Begins

As France entered the Renaissance, a new leavening agent arrived from Flanders and Holland: brewer’s yeast, or levure. This yeast, a byproduct of beer making, worked much faster than a traditional sourdough starter and produced a lighter, whiter, and more delicate bread. This new style became a luxury item, favored by the aristocracy for its novelty and perceived refinement.

This sparked a great debate among bakers. Traditionalists championed the superior flavor, texture, and keeping qualities of pain au levain. They saw yeast-leavened bread as flimsy and tasteless. For centuries, sourdough remained the established standard for quality, everyday bread, while brewer’s yeast was often viewed with suspicion.

| Characteristic | Pain au Levain (Sourdough) | Pain à la Levure (Yeast Bread) |

|---|---|---|

| Leavening Agent | Wild yeasts and bacteria (starter) | Cultivated Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

| Rise Time | Slow (8-24+ hours) | Fast (1-3 hours) |

| Flavor Profile | Complex, tangy, deep | Mild, simple, slightly sweet |

| Shelf Life | Long (several days to a week) | Short (1-2 days) |

| Social Perception | The traditional, authentic standard | A luxurious, delicate novelty |

The Rise of the Professional Baker

This era also saw the formalization of baking as a profession. Bakers’ guilds, known as corporations de boulangers, were established, particularly in Paris. These powerful organizations set standards for quality, regulated the price of bread, and controlled the training of apprentices. This professionalization helped elevate the craft, ensuring that Renaissance era French sourdough techniques were honed, perfected, and passed down with precision.

The Golden Age: Parisian Boulangeries and 19th Century Innovation

The Birth of the Modern Boulangerie

By the 19th century, Paris had become the undisputed epicenter of culinary arts, and baking was no exception. The city’s bakeries, now widely known as boulangeries, became hubs of innovation. It was here that the concept of sourdough’s terroir truly blossomed. Bakers understood that their starters were unique, capturing the specific microbiome of their bakery’s environment. A starter from the Marais district would yield a subtly different loaf from one in Montmartre, giving each bakery a unique and fiercely guarded signature flavor.

Technology and Taste

The Industrial Revolution brought transformative technology to the baker’s door. The invention of steam-injected ovens in the 1840s was a game-changer. The burst of steam during baking allowed for greater oven spring and, crucially, created the thin, crispy, crackling crust (croûte) and tender, open crumb (mie) that are now hallmarks of French bread. Combined with newly available refined white flours, these innovations defined the modern loaf.

However, this era of progress also sowed the seeds of a future decline. The isolation and cultivation of commercial yeast offered bakers unprecedented consistency and speed, beginning the slow shift away from the more laborious, albeit more flavorful, levain. This marks a key moment in Parisian boulangerie sourdough historical development, as traditional French sourdough baking methods began to compete with industrial efficiency.

Decline and Revival: Sourdough in the 20th and 21st Centuries

The Industrial Threat

The period following World War II was one of rapid industrialization. The demand was for speed, volume, and low cost. This philosophy infiltrated the bakery, and traditional pain au levain went into a steep decline. Long, slow fermentation was replaced by fast-acting commercial yeasts and chemical additives. The iconic baguette, once a proud product of craftsmanship, was often reduced to a pale, flavorless loaf that would go stale in hours. For a time, it seemed authentic French sourdough might become a relic of the past.

The Artisan Renaissance

Fortunately, a counter-movement began in the late 20th century. A new generation of bakers, alongside passionate food lovers, rejected the industrial loaf and sought to revive the traditions of their ancestors. This sourdough revival in French bakeries was a powerful statement in favor of flavor, quality, and heritage.

This artisan movement was so influential that it led to government action. In 1993, France passed the “Décret Pain” (Bread Decree). This landmark law legally defined and protected pain de tradition française (traditional French bread). To earn this title, bread must be made on the premises where it is sold and can only contain wheat flour, water, salt, and yeast (either baker’s yeast or sourdough starter). Additives and freezing are strictly forbidden. This law was a victory for quality and a crucial step in ensuring the journey from Roman era to modern French sourdough would continue.

More Than Bread: The Cultural Significance of Sourdough in France

A Taste of Place (Terroir)

In France, the concept of terroir—the idea that food is an expression of the specific place it comes from—is most often associated with wine or cheese. But it applies just as profoundly to sourdough. A levain is a living culture of microorganisms unique to its environment. The wild yeasts in the Parisian air are different from those in the Provençal countryside. The flour milled from local wheat carries its own microbial signature. This makes every authentic pain au levain a true taste of its place.

A Living Heritage

For many French bakers, their starter—the levain-chef or mother starter—is their most prized possession. It is a tangible link to the past, a living heirloom that is fed and nurtured daily, sometimes having been passed down through generations. This starter is a silent witness to history, embodying the baker’s skill and the bakery’s soul.

Ultimately, sourdough’s importance in France transcends its ingredients. It is a symbol of community, a rejection of industrial homogeneity, and a celebration of culinary excellence. The historical significance of sourdough in French cuisine is tied directly to the French identity itself: a deep respect for tradition, an appreciation for simple, high-quality ingredients, and the belief that taking one’s time is essential to creating something of true worth.

Conclusion: The Enduring Rise of French Sourdough

From a practical staple for Roman soldiers in Gaul to a legally protected artisanal treasure in modern France, the journey of pain au levain is a reflection of French history itself. It has survived turmoil, adapted to new technologies, and fought off the threat of industrialization to re-emerge as a cherished symbol of national gastronomy.

Its story is one of resilience and authenticity. It reminds us that some of the best things in life cannot be rushed. The timeless appeal of French sourdough lies not just in its incredible flavor and texture, but in its simple, honest ingredients and the rich, complex history baked into every single loaf.

A high-quality glass container is essential for maintaining your sourdough starter, allowing you to monitor its activity and health while keeping it fresh. Sourdough Starter Container Glass. This complete starter jar kit provides everything you need to begin your sourdough journey, including a wide-mouth jar and helpful accessories. Sourdough Starter Jar Kit. Monitoring temperature is crucial for sourdough success, and a reliable thermometer helps you maintain the ideal conditions for your starter. Sourdough Starter Thermometer. A dedicated warmer mat ensures your starter stays at the perfect temperature, especially important in cooler environments. Sourdough Starter Warmer Mat. Precise measurements are key to consistent sourdough results, and a digital kitchen scale ensures accuracy in every recipe. Digital Kitchen Scale. Testing pH levels helps you understand your starter’s health and activity, giving you insights into its fermentation process. Sourdough pH Test Strips. An established starter culture from around the world can jumpstart your sourdough baking with unique flavor profiles. Sourdough Starter Culture International. Wide-mouth glass jars with secure lids are perfect for storing and feeding your sourdough starter while keeping it visible. Glass Storage Jars with Lids. A cast iron Dutch oven creates the perfect steam environment for achieving that coveted crispy, golden sourdough crust. Dutch Oven Cast Iron Sourdough. A banneton proofing basket helps your dough maintain its shape during the final rise while creating beautiful patterns on your loaf. Sourdough Banneton Proofing Basket. A scoring lame with sharp blades allows you to create beautiful decorative patterns and control how your bread expands during baking. Scoring Lame with Blades. A bench scraper is an essential tool for handling sticky dough, dividing portions, and cleaning your work surface. Bench Scraper Dough Cutter. High-quality parchment paper prevents sticking and makes transferring your dough to the oven effortless. Parchment Paper Baking Sheets. A sturdy cooling rack allows air to circulate around your freshly baked bread, preventing a soggy bottom and ensuring even cooling. Wire Cooling Rack Stainless Steel. A baking stone or steel provides consistent heat distribution, helping you achieve professional-quality sourdough with a perfect crust. Baking Stone Pizza Steel. A comprehensive sourdough cookbook provides detailed recipes, troubleshooting tips, and techniques to elevate your baking skills. Sourdough Bread Cookbook. This artisan baking guide offers advanced techniques and recipes for creating bakery-quality sourdough at home. Artisan Sourdough Baking Book. A detailed starter guide helps you understand the science behind sourdough and troubleshoot common issues. Sourdough Starter Guide. Professional bread baking books offer insights from master bakers, helping you refine your technique and expand your repertoire. Professional Bread Baking Book. Understanding the science behind sourdough fermentation helps you make informed decisions about feeding schedules and temperature control. Sourdough Science Book. A techniques book provides step-by-step instructions and visual guides for mastering various bread-making methods. Bread Making Techniques Book. A troubleshooting guide helps you identify and fix common sourdough problems, from weak starters to dense loaves. Sourdough Troubleshooting Guide.

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.